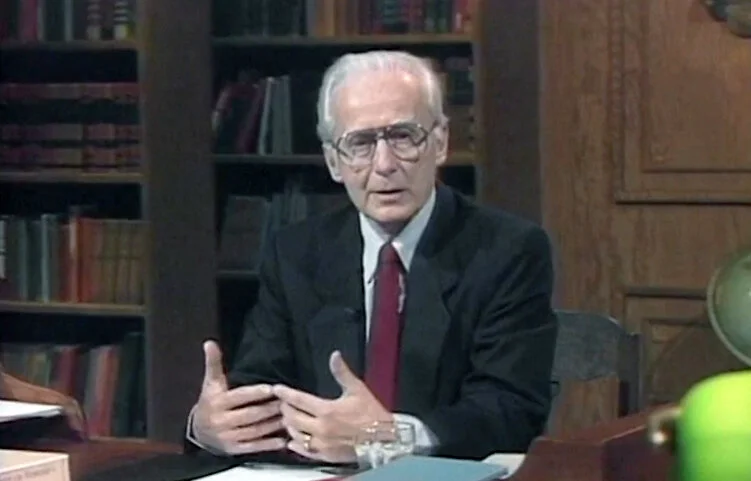

Dr. Ralph McInerny, Founder

Catholic Thinkers was founded as International Catholic University by Dr. Ralph McInerny of the University of Notre Dame. This reflection from Notre Dame Magazine, by his student and Catholic Thinkers board Member Christopher Kaczor, captures something of what Ralph meant to so many people.

“Ralph McInerny’s middle name was Matthew, but it might as well have been Magis, Latin for “more.” The beloved Notre Dame professor taught for more than 50 years, wrote more than 50 books in philosophy and other disciplines, penned more than a thousand essays, short stories, columns and poems, authored more than 90 fiction books, and directed more dissertations than anyone in the history of Notre Dame, 47 to be exact.

When I mentioned to my mother that his funeral included 28 priests and a military color guard playing taps because he was also a Marine, she responded, “Is there anything that man didn’t do?”

His academic achievements are well known — eight honorary doctorates, presidential and pontifical appointments, Gifford Lectures and teaching stints from Argentina to Oxford. His man was, of course, Saint Thomas Aquinas, but not only Thomas. The New York Times obituary noted that Ralph “wrote on the sixth century philosopher Boethius, the 12th-century Spanish Arabic scholar Averroes and later thinkers and theologians, including Cardinal Newman, Kierkegaard, Pascal and Descartes.”

The Los Angeles Times obituary focused on him as “the prolific author of approximately 100 novels. Beginning with Her Death of Cold in 1977, he wrote more than two dozen mysteries featuring Father Dowling, which led to the 1989–91 Father Dowling Mysteries TV series starring Tom Bosley.”

Indeed, The Times of London was not the first place to note Ralph’s extraordinary productivity. “George Orwell, who famously, and wrongly, concluded that the Billy Bunter oeuvre was too vast to have been written by one man (Frank Richards), would have had a similar problem with the output of Ralph McInerny, the American Catholic scholar and writer of detective fiction.” But Ralph was much more than a prolific author.

Part of the “more” — unquantifiable but no less real — was how Ralph treated people and how they responded to him. Among his students, he commanded universal respect.

One might think such a prolific author would neglect his students; au contraire (a McInerny habit was to end sentences in academic lectures in Latin or French). He was my dissertation adviser, and at the time he also advised about eight other students. He was available for us virtually every afternoon in his seventh floor office in the Hesburgh Library’s Jacques Maritain Center. If we gave him a dissertation chapter, he’d have it back to us like a serve in tennis (a line from Thurber that Ralph liked to quote). He gave us laptops. He arranged for extra funding (many of us had two or three kids, and none of us made more than $10,000 a year). He took us out to lunch — The Great Wall of China and the University Club were favorites. He’d give us copies of his scholarly books and his mystery novels. He helped get us jobs.

Most of all perhaps, he provided a living model of a philosopher, a mentor, and a man who embodied virtues and commitments that inspired us all.

I was Ralph’s teaching assistant for his undergraduate course, The Thought of Aquinas, which was my first class in Thomistic thought. He began each class with an “Our Father” (in English or Latin) and ended with a “Hail Mary.”

During my undergraduate days at Boston College (fear not: I’ve repented, and re-affirm my conversion at every BC vs. ND football game), I had been assigned to read Karl Marx in three different courses but was never once given a page of Saint Thomas. Ralph taught me — in that class and also in his many books — a great deal about the relationship of faith and reason, about ethics, and about God. More important, he prompted me to fall in love with Aquinas.

It was also there I first heard the words, words he loved to repeat, from the French writer Leon Bloy, “There is only one tragedy in life: not being a saint.” Though not without moments of deep sadness, Ralph’s life was no tragedy. Indeed his work, his friends and his faith gave him a joy that radiated to others.

Ralph’s joie de vivre manifested itself in a ready smile and a quick wit. Even from his youth, he delighted those around him. In his autobiography, I Alone Have Escaped to Tell You, he writes about being in first grade and not yet having mastered the mystery of R. “My teacher, Sister Mary Electa, would take me up the hall to the other nuns, and I would be put through a little ritual. What is your name? Walph. What are your brothers’ names? Woger and Waymond. There was nothing cruel in this; they obviously found my lisping cute, and I would be hugged and taken back to my desk.”

London’s Daily Telegraph noted, “An inveterate punster, he liked to give his mystery novels titles like Body and Soil, Frigor Mortis and Law and Ardour. One of his books on St. Thomas Aquinas was subtitled A Handbook for Peeping Thomists.” To those titles, we could add such others as Mom and Dead, Celt and Pepper, Good Knights and Lack of the Irish (a book he kindly dedicated to my wife, Jennifer, and me).

When he was still in his 60s, Ralph joked to me about his mortality, “I no longer buy green bananas.” About a host who did not leave him any time for himself, “He’s rather adhesive.” About what he would like to say to a scholar with prolific but narrowly focused writing, “I see you have another book out. What are you calling it this time?”

Ralph called forth the best from us by seeing it in us before we did. After a lunch at Antoine’s in New Orleans with Mortimer Adler, Ralph wrote, “I felt like a rustic nephew being treated by a rich and cosmopolitan uncle.” Around Ralph, I always felt like that rustic nephew, with the addition of a speech impediment. Whether it was in my doctoral comprehensive exams, a public lecture (at his invitation) at Notre Dame or at a talk at the Gregorian in Rome, he had the habit of sitting in the front row and asking the first question of me, which I never failed to fumble. Nevertheless, he seemed to abound in invitations.

Once when he was going to be absent, he asked me to guest teach the Ph.D. graduate seminar I was taking from him. He invited me to work with him on various projects — an assistant editor of Catholic Dossier, a copy editor of Maritain’s Degrees of Knowledge, a board member of the International Catholic University and a co-author of An Illustrated Life of Aquinas (a rare uncompleted project). He was the first scholar to cite me in print, and for some time I thought he’d also be the last. He was so extraordinarily kind that I told my wife he must be the uncle of my Minneapolis-born birth mother, whom I had not yet met.

Days before my dissertation defense in 1996, Ralph had to undergo emergency triple bypass surgery; I claim there was no causal connection. I thought he would miss the graduation ceremony. But there he was, a few weeks later, ashen and weak, but ready to put the doctoral hood over me as well as John O’Callaghan, who would later succeed him as director of the Jacques Maritain Center.

After graduation, he’d gather his former doctoral students, a sizable Schulerkreis, back together for Summer Thomistic Institutes at Notre Dame along with an international cast of young, midlevel and senior scholars. Inspired by Jacques Maritain’s Cercle d’Études, Ralph gave us a forum in which spiritual growth and intellectual pursuits fed each other in a context of camaraderie. It was there that we presented our research, made important professional contacts, and deepened our friendship with him and each other. We prayed together, sang together, ate together and talked late into the night. He and Alice Osberger, his longtime administrative assistant, made it all happen — all at no cost to us.

No doubt Ralph is enjoying his reward, meeting his Maker and, as an incidental benefit, his own model of the intellectual life, Thomas Aquinas. When I think about how I hope to live the rest of my life, he is the model: scholar, teacher, writer, family man, person of faith.”